7.2.14 – SF Gate by Garance Burke, Associated Press

In this May 1, 2014 photo, irrigation water runs along a dried-up ditch between rice farms in Richvale, CA.

Throughout California’s desperately dry Central Valley, those with water to spare are cashing in.

As a third parched summer forces farmers to fallow fields and lay off workers, two water districts and a pair of landowners in the heart of the state’s farmland are making millions of dollars by auctioning off their private caches.

Nearly 40 others also are seeking to sell their surplus water this year, according to state and federal records.

Economists say it’s been decades since the water market has been this hot. In the last five years alone, the price has grown tenfold to as much as $2,200 an acre-foot — enough to cover a football field with a foot of water.

Unlike the previous drought in 2009, the state has been hands-off, letting the market set the price even though severe shortages prompted a statewide drought emergency declaration this year.

The price spike comes after repeated calls from scientists that global warming will worsen droughts and increase the cost of maintaining California’s strained water supply systems.

Some water economists have called for more regulations to keep aquifers from being depleted and ensure the market is not subject to manipulation such as that seen in the energy crisis of summer 2001, when the state was besieged by rolling blackouts.

“If you have a really scarce natural resource that the state’s economy depends on, it would be nice to have it run efficiently and transparently,” said Richard Howitt, professor emeritus at the University of California, Davis.

Private water sales are becoming more common in states that have been hit by drought, including Texas and Colorado.

In California, the sellers include those who hold claims on water that date back a century, private firms who are extracting groundwater and landowners who stored water when it was plentiful in underground caverns known as water banks.

“This year the market is unbelievable,” said Thomas Greci, the general manager of the Madera Irrigation District, which recently made nearly $7 million from selling about 3,200 acre-feet. “And this is a way to pay our bills.”

All of the district’s water went to farms; the city of Santa Barbara, which has its own water shortages, was outbid.

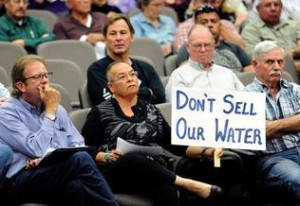

The prices are so high in some rural pockets that water auctions have become a spectacle.

One agricultural water district amid the almond orchards and derrick fields northwest of Bakersfield recently announced it would sell off extra water it acquired through a more than century-old right to use flows from the Kern River.

Local TV crews and journalists flocked to the district’s office in February to watch as manager Maurice Etchechury unveiled bids enclosed in about 50 sealed envelopes before the cameras.

“Now everyone’s mad at me saying I increased the price of water. I didn’t do it, the weather did it,” said Etchechury, who manages the Buena Vista Water Storage District, which netted about $13.5 million from the auction of 12,000 acre-feet of water.

Competition for water in California is heightened by the state’s geography: The north has the water resources but the biggest water consumers are to the south, including most of the country’s produce crops.

The amount shipped south through a network of pumps, pipes and aqueducts is limited by the drought and legal restrictions on pumping to save a threatened fish.

During the last drought, the state Department of Water Resources ran a drought water bank, which helped broker deals between those who were short of water and those who had plenty. But several environmental groups sued, alleging the state failed to comply with the California Environmental Quality Act in approving the sales, and won.

This year, the state is standing aside, saying buyers and sellers have not asked for the state’s help. “We think that buyers and sellers can negotiate their own deals better than the state,” said Nancy Quan, a supervising engineer with the department.

Quan’s department, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation and the State Water Resources Control Board have tracked at least 38 separate sales this year, but the agencies are not aware of all sales, nor do they keep track of the price of water sold, officials said.

The maximum volume that could change hands through the 38 transactions is 730,323 acre-feet, which is about 25 percent of what the State Water Project has delivered to farms and cities in an average year in the last decade.

That figure still doesn’t include the many private water sales that do not require any use of government-run pipes or canals, including the three chronicled by the AP. It’s not clear however how much of this water will be sold via auctions.

Some of those in the best position to sell water this year have been able to store their excess supplies in underground banks, a tool widely embraced in the West for making water supplies reliable and marketable. The area surrounding Bakersfield is home to some of the country’s largest water banks.

The drought is so severe that aggressive pumping of the banked supplies may cause some wells to run dry by year’s end, said Eric Averett, general manager the Rosedale Rio Bravo District, located next to several of the state’s largest underground caches.

Farther north in the long, flat Central Valley, others are drilling new wells to sell off groundwater.

A water district board in Stanislaus County approved a pilot project this month to buy up to 26,000 acre-feet of groundwater pumped over two years from 14 wells on two landowners’ parcels in neighboring Merced County.

Since the district is getting no water from the federal government this year, the extra water will let farmers keep their trees alive, said Anthea Hansen, general manager of the arid Del Puerto Water District.

Hansen estimated growers would ultimately pay $775 to $980 an acre-foot — a total of roughly $20 million to $25.5 million.

“We have to try to keep them alive,” Hansen said. “It’s too much loss in the investment and the local economy to not try.”

###

Read article at www.sfgate.com