Foes say $5 billion project to severely degrade water quality

by Dave Waddell

James Murphy’s ranchland, which he’s owned for 35 years, would be under water if the long-discussed Sites reservoir becomes a reality.

A conceptual rendering of the Sites reservoir west of Maxwell.

If the Sites Project Authority seeks to acquire Murphy’s property to build the reservoir, he’s going to make it as difficult for them as possible.

“I don’t want to sell my land; there’s no reason for me to sell,” said Murphy, a retired rancher who leases his 1,600 Sites-area acres for cattle grazing. “If they condemn it, they’ll have to tear it out of my hands.”

The proposed reservoir is being promoted as means of capturing water in big storms for use during California’s inevitable dry stretches. Sites’ timeline has the project being reviewed by the California Water Commission in 2021 and becoming operational in 2029.

Among Sites’ benefits would be providing water for agriculture, human consumption, recreation, and to help fish and wildlife, its supporters say. Critics of the Sites proposal say it would harm rather than help the environment – potentially causing deteriorations in water quality that are alarming, unexamined, and likely to eventually drown the $5 billion-plus proposal.

Sites is owned by the authority, a public-private partnership of counties and local water agencies formed in 2010. As proposed, Sites would divert water from two existing canals, as well as from a new underground piping system to bring water from the Sacramento River, 14 miles to the east, during periods of peak runoff. The idea is to return the water in the pipeline to the river in dry times for multiple uses, including to aid migrating Chinook salmon.

The project possesses bipartisan political backing, a seeming rarity these days, including the blessings of the Trump administration. Momentum is seen in highway signs touting Sites that have popped up in the Sacramento Valley.

The proposed reservoir would be located about 8 miles west of the Colusa County community of Maxwell in a mountain valley once described as a “natural bath tub.” Sites’ location is about a 90-minute drive both from Sacramento to its south and from Chico to its northeast.

Sites map

Those who oppose the project attack what they see as woefully inadequate study to date on Sites’ impacts, with its general manager acknowledging at a congressional hearing last year that the draft environmental impact report (EIR) was speeded up in order to move the project along.

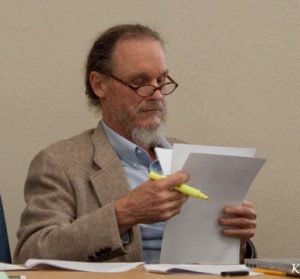

Policy analyst Jim Brobeck: Sites would become a “biological wasteland.”

Some environmentalists opposed to a Sites reservoir question how it can deal with water-quality issues to the satisfaction of California regulators while still penciling out financial advantages for investing water agencies.

Jim Brobeck, a policy analyst for the Chico-based environmental group AquAlliance, goes so far as to predict that Sites, if built, will become a “biological wasteland.” AquAlliance fights what it sees as threats “to the hydrologic health of the northern Sacramento River watershed,” according to its website.

“The project has been considered since the middle of the last century and has never moved forward because it is not feasible economically, environmentally, technically or financially,” argues Brobeck. “But dry years inspire hope in leaders and the public that ‘new water’ can be found in the Sacramento Valley Watershed to meet the demand from the San Joaquin Valley.”

Two sprawling valleys, the Sacramento and the San Joaquin, comprise California’s Central Valley, which roughly stretches 450 miles from Redding to Bakersfield.

Murphy, the retired rancher, said he isn’t losing any sleep over pleas for more water from San Joaquin Valley growers.

“I’m not donating to these big farmers out in the valley,” said Murphy, who lives in Arbuckle. “I don’t think I owe them anything. I’m 82 years old and I want to keep what I’ve got.”

Location of proposed reservoir.

The 17,000 total acres that would need to be acquired to build Sites is mostly ranchland owned by about 25 people. Jim Watson, general manager of the Sites Project Authority, said use of eminent domain “does not have to be adversarial” and can include tax advantages for selling land owners.

“With the property owners, it’s what works best for them,” Watson said. “The acquisition process has a little more complexity and depth than most people realize.”

Water titans invest

While the state and federal governments are Sites’ largest financial supporters, investors currently include 21 local water agencies, of which 11 are in the Sacramento Valley. Two titanic water players — the Fresno-based Westlands Water District and the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California — have bought into Sites, with Metropolitan in February committing $4.2 million for project planning.

That has occurred at the same time some Sacramento Valley water agencies have reduced their Sites’ stakes, due mostly to cost concerns.

Roger Patterson, assistant general manager for the Metropolitan Water District, said the district bought what amounts to a 10 percent ownership of Sites’ water after being encouraged to invest by other project partners. Most significant from Metropolitan’s perspective is that Sites, in its plan to provide water for environmental benefits, could relieve some of the strain on state and federal projects caused by the competing demands for California’s water.

“We want to see the project get built. It’s a good project,” said Patterson, who previously headed up the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation division that operates Shasta Dam.

In the midst of a drought in 2014, Californians passed Proposition 1, which includes state bond financing for water storage projects. Last year, the state Water Commission awarded $816 million to Sites in Prop. 1 funding – more than any other project but only about half the amount it originally sought. At the time, Watson characterized the funding level as “an opportunity lost” to provide additional cold water from Sites to assist salmon populations trekking the Sacramento River.

As for the federal government, Watson pegs the Bureau of Reclamation’s current total commitment to Sites at “over $1 billion towards construction costs and represents over 100,000 acre-feet per year” that would be used principally to help the salmon.

“This water is intended to benefit salmon runs by having Sites reservoir operate to enable Shasta (Dam) to maximize its cold water pool – especially in dry years,” Watson said.

A basic cost-benefit comparison of the Sites plan with another longtime proposal in the north state to increase water storage – raising Shasta Dam by 18½ feet – shows Sites would yield much less bang for the buck. Sites would provide a maximum of 500,000 acre-feet per year at a projected cost of $5.2 billion to build. The plan to raise Shasta Dam, which also has advanced during the Trump administration, would add up to 634,000 acre-feet in peak years for a purported price tag that is much less: $1.4 billion. (One acre-foot equals 326,000 gallons.)

Still, a bipartisan political push for Sites is ongoing in Washington, D.C., as two veteran north state politicians – Reps. Doug LaMalfa, R-Richvale, and John Garamendi, D-Walnut Grove — continue to seek tax funding for the project. In February, the two congressmen introduced the Sites Reservoir Project Act (HR 1453) that would direct the Bureau of Reclamation to finish a feasibility study of the proposed reservoir and, if Sites is deemed feasible, provide additional funding and technical aid. Watson told ChicoSol that Reclamation is “working to finalize” the feasibility report this year.

First congressional district Rep. Doug LaMalfa

Third congressional district Rep. John Garamendi

Boosting Sites’ chances at least in the short term is that David Bernhardt, a former lobbyist for both the oil industry and the Westlands Water District, has been promoted to the top of President Donald Trump’s Department of Interior. Claims have mounted against Bernhardt alleging use of his Interior positions to help Westlands, which is a big backer of raising Shasta Dam.

Draft EIR accelerated

Watson was hired to manage Sites in 2015 at a reported beginning salary of $225,000. He previously worked for the Westlands Water District. At a congressional hearing on Feb. 14, 2018, in an exchange with Rep. LaMalfa, Watson described the project’s environmental strategy while noting that 33 agencies had invested $18 million up to that point in Sites.

General Manager Jim Watson

“We used that money to accelerate the project, specifically the environmental document,” Watson told the House Subcommittee on Water, Power and Oceans. “We also took a strategy different than the state or (federal governments) by not trying to do a litigation-proof environmental document. Get what has been known and collected over the last 15 years … out for public comments and then advance the project by incorporating and responding to the public’s comments.”

The AquAlliance’s Brobeck said nearly 1½ years have passed since some highly critical comments about the adequacy of the project’s draft EIR were submitted, with no response yet from Sites.

Sites reservoir’s so-called “footprint” would ultimately inundate and denude a watershed of about 15,000 acres.

“I think the Sites project is … unfeasible, but continuing to plan (and) produce glossy promotional events gives politicians and water marketers the PR gain that they are doing something,” Brobeck said.

Watson told ChicoSol recently that Sites provided a relatively generous 150 days to respond to the draft EIR. Sites’ response to comments on the EIR will be provided in 2019, he said.

“That is going to start this year,” Watson said. “It’s time to respond to the comments. … We’ve received some very good comments on various topic areas.”

At capacity, as envisioned, Sites reservoir’s so-called “footprint” would ultimately inundate and denude a watershed of about 15,000 acres. It’s a landscape described by Brobeck as a mix of “oak woodlands, grassland, wetlands, riparian habitat, and croplands.”

“Once you flood something and hold water once, it kills the vegetation,” Brobeck said. “It’s going to be dead for any trees and any stabilizing roots for a long time. … And when it’s not full it’s even worse,” as accelerated runoff and extreme erosion “turn the footprint into a biological wasteland.”

Area where reservoir would be built.

Brobeck argues that water flowing to the Pacific Ocean is not “wasted,” as LaMalfa and others frequently contend, but rather needed to improve the environmental health and counter the devastation to the fisheries of the San Francisco Bay Delta Watershed.

Mineral levels high in water

Supporters of Sites say the project would save precious water for use in dry times, including for crop irrigation, domestic water consumption, and helping fish and wildlife. Foes, however, predict it would produce declines in water quality that could harm living things and degrade Sacramento Valley agriculture.

The AquAlliance points to a 27-page response from Jerry Boles of Chico that addresses what Boles sees as numerous shortcomings related to water quality in the draft EIR produced for Sites in 2017. Boles is a former chief of the water quality and biology section of the Northern District of the state Department of Water Resources office in Red Bluff.

While in that role, Boles conducted tests in what would be the “source waters” for a Sites reservoir and found “high concentrations of a number of metals.” These substances, described as “the bad metals” by the AquAlliance’s Brobeck, are mostly naturally occurring. They include aluminum, arsenic, cadmium, chromium, copper, iron, lead, manganese, mercury, nickel, selenium and zinc. The metal concentrations “exceed many water quality criteria and standards” and would detract from all of the benefits that Sites purports to provide, Boles wrote.

Sites’ Watson said he’s aware of concerns about selenium in the soils below the Coast Range where the reservoir would be located. To some Californians, selenium is associated with the killing and deforming of wildlife in the Kesterson National Wildlife Refuge on the west side of the San Joaquin Valley in the 1970s. Surplus ag water with high levels of selenium was the culprit at Kesterson, which, like the Sites’ site, is located on the western edge of the Central Valley.

Watson told ChicoSol that Sites could provide water for existing Sacramento Valley wildlife refuges along the Pacific Flyway, as well as to fields adjacent to those refuges “to extend their reach.”

“Initial studies show the selenium (at Sites) is not at levels that would create a health hazard,” Watson said. “But we have to do additional studies to convince ourselves” there are no dangers.

Murphy, the longtime ranch owner, said he’s not aware of any health problems ever from his livestock drinking from area creeks.

“My cattle drink out of it and there’s nothing wrong with them,” Murphy said. “They all do pretty good on it.”

Due to its soil composition, the canyon in which Sites would be located is less conducive to crop growing than the more fertile Sacramento Valley lands to the east. As proposed, the reservoir would be created by the damming of what Watson described as two “seasonal” creeks – Funks and Stone Corral. The often sizzling summer temperatures on the west side can mix with some ferocious winds, which would heighten evaporation in a Sites reservoir and increase the mineral toxicity of its water, critics say.

Watson contends that the project offers “tremendous value for the salmon runs” in being able to pipe cold water to the Sacramento River at critical times to help the fish. That benefit assumes that Sites would be like other large Central Valley reservoirs that “stratify” – meaning the water is colder at lower depths. Watson said Sites would have the capacity to access that colder water to aid the salmon, while sending its warmer water out to farming operations.

However, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW), which has regulatory authority over how much river water Sites could extract, says the project’s water temperature assumptions need more study.

“Most large reservoirs in the Central Valley receive runoff from snowpack, which is largely absent from the Funks and Stone Corral watersheds,” the CDFW said in a less-than-encouraging Jan. 12, 2018, letter responding to the draft EIR. “In addition, the proposed Sites Reservoir will be located in a shallow canyon, which will create a large reservoir with a large surface area making it more vulnerable to mixing from high winds.”

Chief among the CDFW’s worries in its 24-page letter are the potential impacts of water diversions to declining salmon populations. Spring-run Chinook salmon have been listed as endangered by the federal and state governments for 20 years.

While the consultants who prepared the draft EIR found there would be “no cumulative impacts” from Sites, the “CDFW considers that the additional extraction of water … would exacerbate concerns and generate cumulatively considerable impacts.”

The report by Boles, the retired water quality official, argues that, given the conditions, water released from Sites to the Sacramento River will be too warm or otherwise unsuitable for supporting cold-water fisheries.

Boles contends that “the little analyses presented in the EIR misconstrues, misinterprets, and ignores water quality data that amply demonstrate” the potential for major environmental impacts from Sites. The water-quality section of the EIR draft, Boles writes, “must be completely rewritten with an objective analysis of the data and potential adverse impacts to water quality both within the (Sites) reservoir and to downstream resources in the Sacramento River.”

Watson equated his job as Sites manager with the peeling back of an onion, examining one issue at a time.

“If you find a fatal flaw, the project off-ramps,” Watson said. “So far, we haven’t found one.”

Dave Waddell is a contributor to ChicoSol. This story was reported and written with support from Ethnic Media Services.

View article at http://chicosol.org/2019/05/28/sites-reservoir-become-biological-wasteland/.