A staggering economic and environmental problem festering for three decades in the southern San Joaquin Valley would be addressed by a secret deal reached between the Obama administration and farmers — one that is sounding alarms for Bay Area lawmakers.

A staggering economic and environmental problem festering for three decades in the southern San Joaquin Valley would be addressed by a secret deal reached between the Obama administration and farmers — one that is sounding alarms for Bay Area lawmakers.

The deal would retire 100,000 acres of farmland damaged by salt and selenium in the Westlands Water District, an arid, 600,000-acre patch of farms running along Interstate 5 from Mendota in Fresno County to the Kings County town of Kettleman City. About 600 farms there produce $1 billion in food each year.

Congress agreed in 1960 to bring water to the area with the promise that the government would build a drain for the toxic brew that leaches from the mineral-rich soil. The drain was only partly built, due to opposition from the East Bay communities where the water was to be dumped.

Instead, the drain stopped at a place called Kesterson, where federal officials turned the ponds into a national wildlife sanctuary. In 1983, drainage water contaminated by salt, boron and selenium caused an environmental catastrophe there, killing thousands of birds and fish and causing grisly deformities among chicks.

The drain was closed, but decades of litigation followed in which Westlands sued the government for failing to provide farmland drainage. The courts have agreed that the government has an obligation to fix the problem, and the Obama administration and Westlands have now agreed on a plan.

Congressional approval

Details of the deal between Westlands and the federal Bureau of Reclamation have not been revealed to members of Congress, who would have to approve it. But according to a short “principles of agreement” document that has been made public, the deal would forgive $342 million in federal debt that Westlands owes for construction of the 1960s extension of the Central Valley Project to deliver water to the San Joaquin Valley farms.

In return, taxpayers would be relieved of an estimated $2.7 billion obligation to remove the contaminated water that results from the irrigation. Resolution of the drainage problem would be left to Westlands farmers.

Westlands would not have to retire any land beyond what it has already taken out of production because of salt buildup, even though federal agencies have recommended retiring more than 300,000 acres, or half the district, on the grounds that the only way to end the drainage problem is to stop irrigating the land.

Critics think Westlands should be required to retire much more land if taxpayers bail out its debt.

The more land is irrigated, the more pollution is produced, “at which point you need to treat the water in some way that’s very expensive,” said Michael Wara, a Stanford University law professor and former geochemist. “Or you cause Kesterson Wildlife Refuge 2.0.”

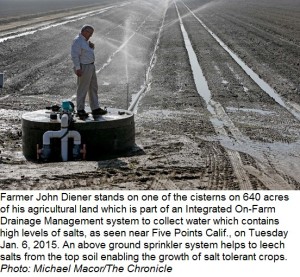

“We’ll take care of our own issues,” replied John Diener, a Westlands farmer who has won conservation awards for his efforts to deal with irrigation drainage on his 3,000-acre Redrock Ranch at Five Points in Fresno County.

‘Glunked up’

“When the government gets involved, as we found out, it just gets glunked up and so cumbersome, by the time you get done, you spend so much money just getting to the party that you go bankrupt,” Diener said.

Westlands officials did not respond to requests for comment and administration officials declined to discuss the deal, citing the pending litigation.

Rep. Jared Huffman, D-San Rafael, criticized parts of the deal that could give Westlands farmers more secure water rights, and accused the district of “a three-decade strategy (of) endless litigation, endless lobbying and endless PR” to “leverage concessions from taxpayers.”

Huffman sits on the House Natural Resources Committee and would be among the Democrats leading opposition to any deal. He said he hopes to “shine a bright light on the huge giveaways that appear to be part of this.”

Westlands allies bristle at the suggestion that additional farmland should be retired. They point out that many valley farmers have switched from vegetables to wine grapes, almonds and other permanent crops that use less water than row crops, and pistachios, which tolerate saltier soil.

“A lot of our critics are living in a drainage world that’s long gone,” said Dennis Falaschi, general manager of the neighboring Panoche water district to the north.

Less pollution

When water was cheap and lavished on low-value crops, there was a lot of waste drainage, he said. Now water is costly and used sparingly, Falaschi said, reducing the amount of polluted waste.

“Just the conversion alone from row crops that took flood irrigation to permanent crops on drip irrigation in itself almost solves the drainage problem,” Falaschi said. “If you talk about just retiring land, do people really understand the environmental disaster that would be caused, with dust storms so bad you couldn’t even traverse Interstate 5?”

Diener said the retirement of about 110,000 acres of the most problematic lands has greatly diminished the drainage problem. In addition, sharply reduced water deliveries during the drought has reduced the need for drainage.

Although it is often hailed as some of the world’s most productive farm country, Westlands’ chief virtue is its temperate climate, not its land.

The soil consists of an ancient seabed full of minerals perched atop an impermeable layer of clay. Irrigation leaches the minerals, and the clay barrier traps the water. Unless it is drained, the land is ruined.

Salt buildup

Since ancient times, salt buildup has been recognized as a problem tht is endemic to all irrigated farming on arid lands. In Westlands, some areas are dusted with “San Joaquin Valley snow,” crystallized salt where no vegetation can grow.

Critics say Westlands is in the wrong place and should never have been irrigated. In a blistering full-page ad in the Los Angeles Times in December, Westlands President Don Peracchi retorted that if that’s the case, then Los Angeles is also in the wrong place.

Farmers and their allies said the drainage problem is vastly overstated and that promising new technology will solve the rest.

Salt-tolerant crops

Diener, for example, has created a system that reuses water on a progression of salt-tolerant crops, including forage grasses and even cactus. As the water grows briny, he hopes to harvest the salt for sale to glass makers and other industrial users. “We actually clean the soil up and recycle the water,” Diener said.

A pilot desalination plant in the Panoche district built by Bay Area startup WaterFX uses solar energy to process drainage water. The system produces distilled water and solid salts and minerals that have value for industry, all for $450 an acre-foot, half the cost of conventional desalination.

“We actually think we can solve the drainage problem,” said company founder and chairman Aaron Mandell. He said the system is well suited to places like Westlands, where farms are undergirded by a vast system of drain pipes, much like a city sewer that can collect the water.

“Some of these districts that have a lot of drain water could actually become net producers of water,” Mandell said. “There’s no limit to the scale we can achieve with this.”

But the full-scale plant scheduled to be built in 2015 would deliver just 2,240 acre-feet annually, a tiny fraction of the Westlands contract for more than a million acre-feet of water from the Central Valley Project. Even Mandell’s plan to process 10 times that amount in five years by building other plants would fall far short of the water that Westlands farms need.

Huge cost

Stanford’s Wara said that if the new technology proves workable, “that would change the ballgame for water in the western United States.” But he was skeptical, noting among other things that the capital cost of plants big enough to handle Westlands drainage would be huge.

The WaterFX demonstration plant was funded with $1 million in state grants and the new plant will cost $30 million; the company is looking for investors.

The Obama administration’s goal is to put an end to the government’s obligation to deal with the problem.

The Bureau of Reclamation has settled several San Joaquin Valley drainage claims for large sums in the past. The bureau has also consistently charged farmers less for federal water than is needed to pay the cost of Central Valley Project. That’s why Westlands has $342 miillion in debt that the administration plans to forgive.

Water districts like Westlands are quasi-public agencies created when a group of water users, in this case farmers, form an agency to buy water from the government. They are governed by a board of directors — the Westlands panel is made up of large landowners, many of them from families who settled the area. The district was formed in 1952, and is the largest water district in the nation, covering about 1,000 square miles. The district derives its revenue from water sales to its farmers.

Wara said Westlands farmers probably cannot repay the debt the district incurred for bringing Central Valley Project water to the district, because environmental restrictions have led to water cutbacks.

For that reason, he said, it makes sense for the government to write off the debt as a “stranded asset.” The question is what taxpayers should demand in return in the way of land retirement.

Dealing with damage

Critics also want the deal to spell out clearly what Westlands plans to do with the polluted drainage. Westlands is developing solar-energy parks on some of the impaired land.

Wara described the Bureau of Reclamation as an agency so close to its water contractors that it “simply cannot be trusted to ‘negotiate’ with its ‘clients’ without some form of oversight or transparency. If that isn’t happening, and it sure doesn’t seem like it is, then that’s a big problem.”

Several Westlands officials are former bureau officials, Wara said. He also questioned how Westlands can be held responsible for the astronomical cost of handling the drainage once the government washes its hands of the problem.

“Let’s just say it’s $2 billion,” Wara said. “It’s not clear to me how you would structure a contract that would force Westlands to spend the money necessary to really manage the problem on the lands they continue to irrigate.”

Even with such high-value crops as wine grapes and almonds, he said, “how much of that money can they really spend on this drainage issue … before farmers decide to get out of the business of farming?”

Diener said the drainage problem “costs money, no doubt. But what’s agriculture worth?”

By Carolyn Lochhead, Washington correspondent for The San Francisco Chronicle, e-mail: clochhead@sfchronicle.com

Click here to read full story with more pictures at SFgate.com.